The classic gin and tonic is a staple in African history but has taken on a new life as artisans are concocting new recipes for the modern palate. We sat down with ‘distilleress’ Jessica Henrich of A Mari Ocean Gin to learn more about the history of this incredible cocktail and how it became an integral part of the South African culture.

So this story begins, as many interesting ones do, with a drink. But not just any drink. A drink that has followed an evolution alongside its drinkers, a drink that as come through pestilence and plagues, through wars, through continents. A drink that has been the stalwart of sailors and the champion of soldiers. A drink prescribed by doctors, heralded by politicians.

A drink, in short, that has held captive the minds and imaginations of centuries of humans. And despite this rich history, it has a very short name. Gin.

The first records of gin making go back to the middle ages, and the earliest written reference to Genever appears in the 13th-century encyclopaedic work Der Naturen Bloeme (translated from Dutch as “The Flower of Nature”), but it seems no one bothered to write the recipe down until the 16th century, where it’s found in Een Constelijck Distileerboec, a manual made for distillers in the Low Countries. At the time it was a medicinal libation, used for everything from gallstones to gout- although the latter seems like an extraordinarily bad idea.

By the 17th Century, Genever had really taken off in Holland, and while still being prescribed as medicinal, it started making inroads into shall we say, home medication. This early gin was however vastly different to its modern-day cousin.

Traditionally, Genever was produced by distilling Malt wine to 50% ABV. The resulting spirit was fairly horrible, due to both primitive distilling techniques, and unsophisticated palates, so the distillers added various spices, herbs and sugar to mask the nasty flavour. The most pungent- and hence effective flavour was juniper, in Dutch ‘Jeneverbes’, which lead to the name Genever. Juniper was also prized for its medicinal purposes, so double whammy, it was booze AND it was good for you. That is, if you didn’t go blind drinking it. The blindness, by the way, came from severe alcohol poisoning as the impurities in alcohol can be lethal if not correctly distilled.

The Dutch absorbed much of this Genever production into their shipping system, partially to fend off scurvy in the sailors, partially probably for entertainment on the seas. The term ‘blind drunk’ was probably coined around then. The rest of the world started tasting Genever. It’s fame spread.

At the same time, William of Orange took over the throne in England, and in his more liberal, Dutch wisdom decided to be less puritan on distilling, and drinking, and basically said, ‘Hey English people, lets all have a little bit of a razzle because if you’re drunk/and or blind you’re less likely to revolt.’ He relaxed the laws on distilling. The English lower classes thought this was a jolly good idea, and set to making Genever with gusto.

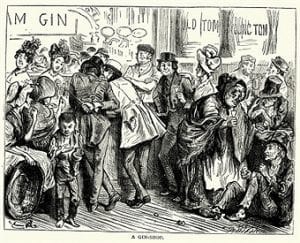

Vintage engraving of a scene from the Charles Dickens’s novel Sketches by Boz. A Gin Shop.

Also, unfortunately, with Turpentine… A lot of people subsequently went blind and mad. Captured so tellingly in Hogarth’s Gin Lane, this type of home-brew gin earned the moniker, “mother’s ruin” due to its amazing ability to cause impotency in men and sterility in women.

At this point in history, the Dutch had created lots of blind sailors and the English upped the ante by creating lots of poisoned, insane poor. So far, gin is doing very well in terms of helping humanity move forward.

English troops fighting alongside the Dutch in the Thirty Years’ War also noticed that the Dutch soldiers were extremely courageous in battle. This bravery became attributed to the ‘calming effects’ of the genever that they sipped from small bottles hanging from their belts. By ‘calming effects’ I mean the boys were on the lash and so plastered they didn’t care what happened to them. Anyone having watched drunk boys in a bar fight will understand this theory well. English soldiers returning home brought back even more enthusiasm for this drink, and that’s where we get the term ‘Dutch courage.’

So we can thank the Dutch for the ancestor of gin, but who is responsible for the modern day incarnation? Well, that would probably be the English. We all know that the English, where they lack in culinary endeavours, are really quite good at drinking.

At this point in gin’s murky past, Aenas Coffey invents the (humbly named) Coffey (Column) still which created cleaner and better spirits and less chance of poisoning. Yay. This distillation method pruned down the necessity for heavy sugaring and heavy botanicals. It produced a lighter, more flavorful gin. Aenas was a baller. He should be heralded as a ‘ginius,’ if you’ll excuse the pun. Anyway, onwards with the story, and enter the London Dry Gin. So called because predominantly produced in London and a less sweet version compared to the older style, genever-like Old Tom gin.

And so gin reinvents itself again and goes back to sea, this time with the Brits.

Officers of the British Navy were paid a portion of their wage in gin (lucky devils). Alcohol on board Naval ships was decreed to be a minimum of 57.7% ABV to ensure gunpowder stocks stayed flammable if contaminated by any leaky gin barrels. Never ones to be short-changed, sailors would light a small amount of gin-soaked gunpowder, therefore obtaining ‘proof’ their ration had not been watered down by a scrimping Navy. Hence, proof.

As the British Empire expanded, malaria was a huge concern. The only known remedy was quinine, but this is a horribly bitter substance. Some enterprising individual mixed the quinine with recently discovered carbonated water, and we have the early version of tonic water. No fun to drink on its own, an even more enterprising individual added Gin (my money is on a naval officer). The Gin and Tonic now appears. The troops stationed in any tropical clime soon adjusted to this new libation and the G&T became a staple drink of the colonial settlers. Again, in the name of medicinal purposes…

So, did Dutch Genever start the juniper berry rolling in Africa or did the Brits bring it along in the 19th century? According to some sources, Gin got to South Africa courtesy of the Dutch. They are, undoubtedly, the originators of that precursor to modern day gin, Genever.

The question is, however, does Genever really represent the modern day take on gin? Or was that version of gin brought here when the Brits arrived, all red-coated, sweating and clutching their G&Ts to fend off Malaria? There’s no way to know for sure… Either way, we know that it took on a totally new persona once it hit the African shores.

South Africa boasts one of the singularly most interesting floral kingdoms in the world, and the Western Cape specifically holds five of South Africa’s 12 endemic plant families and 160 endemic genera. In terms of gin production, the playground of botanical flavours that surrounds this area is one of the most diverse in the world. For a distiller, it is like being let loose in an immense sweet shop and told to taste everything. It is, in short, an utter delight.

I say this with some experience, as one of the founders and distillers of A Mari Ocean Gin. We spend a lot of time wandering up and down the coastline, or up and down the mountain, tasting and smelling plants and exclaiming a series of constant ‘wows.’

We decided to take the ginvolution one step further, and not only play with botanicals but change the water used in the distilling process. We use Atlantic Ocean water in our distillation, and as far as I know we are the only gin in the world made with ocean water. Hence the name, A Mari, which means ‘ from the sea’ in Latin. The minerals in the seawater actually affect the distillation process, extracting the flavours from the botanicals more efficiently and producing a beautiful, citrus-forward and spicy, floral gin.

In terms of South African offerings, as well as all the beautiful fynbos-driven gins there are some really exciting alternative gins being made in Cape Town. Roger Jorgensen of Jorgensen’s distillery produces a pepper gin. Bloedlemoen Gin uses blood orange. Pienaar and Sons make a gin out of maize and oriental spices. Musgrave uses roses. Hope on Hopkins has a fabulous modern distillery in Woodstock and produce three beautiful gins. Durbanville distillery uses cold distillation in their gin. It’s all heady, exciting stuff. There are gins made in Johannesburg, in Durban, in the Karoo. South Africa is a really exciting space for gin right now.

So this magical, mad spirit continues to evolve and refine its personality, and the plethora of flavours available continue to delight. Long live Gin, and cheers to seeing what it brings us next…